To serve thy Chair

I am about to turn over the chair

of our university Writing Across the Curriculum Committee (WACC) to the

next person. When I took on the job, I thought long and hard about how to be an

effective leader calling on my experience teaching group work to students, what

I know about human nature from sociobiology, and even what I have gleaned from

reading the great books on political philosophy. In the end, it went very well. We went from being demoralized with a 20 year backlog of courses to renew to being caught up and expanding

pedagogical support in teaching writing to faculty. To help others who need to

take on a committee chair or leading a group here is a guide to what I think

are the main factors for this success.

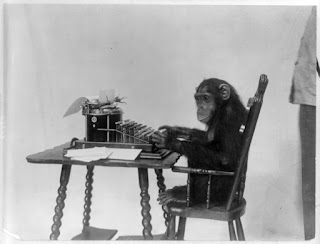

The foundation for leading is to

accept and work with our monkey brains. I know some people have problems with

sociobiology, but sorry folks, we are all just very clever chimps. Like all

other animals, Darwinian self-preservation is the number one biological motivator.

People will only act altruistically for some higher cause. If you want your

group to work together, then you have to identify that cause. Selfish behavior

may seem more easily manipulated, but this is a dangerous trap for a group

leader to fall into. With any complex task requiring group work the

number of possible outcomes makes the impact on your group members so

unpredictable as to guarantee they will turn on the group as soon as it is to

their advantage. If you have the power of life and death over your group

then fine, use fear over love as Machiavelli said, but in low stakes volunteer groups

you need to remember you are working with people who feel physically secure

enough to ignore you. The best strategy is to identify that higher goal

and ask your group members to sacrifice their time and energy to reach that

goal. Always bring the discussion back to the higher principle guiding the

group when there is any sign of selfishness. Anyone that you have to manipulate

through their self-interests are a net detriment to your group and need to be

removed as soon as possible.

The next lesson from sociobiology

is that our brains are evolutionarily wired to be exquisitely sensitive to the

slightest challenge to our social status. Remember that we were social animals

living in dominance hierarchies before we were human. Pride is then our

strongest social instinct. Pride is also the single most common problem in

groups. Whenever there is a dispute, always ask is the fight about the actual

work under discussion, or is the topic under discussion simply being used as

ammunition in a dominance hierarchy fight? Nine times out of ten disputes are

more about hurt feelings and pride rather than the matter at hand. The trick is

to bring the conversation back to the topic at hand and assuage hurt feelings.

I am always amazed how much subtext in committee meetings is about preserving

pride or establishing superiority.

On the positive side, pride is the

number one most ethical and most important motivator a leader should use to get

group members working. Pride is self-love and healthy happy people love

themselves and want to act in a manner they are proud of. The goal for any

leader is to have your group working for the motivating ideal in a way that

everyone is proud of their contribution and know that their specific

contributions are valued. This is where another concept for sociobiology comes

in, the division of labor. If we acknowledge that everyone is different, then

some people are better at some things than others. That is the fact that a good

leader uses to make the team greater than the sum of its parts. By publicly

acknowledging that a group member is better than other members in one or a few

characteristics, that member will be proud of their contribution. Other members

can then be proud by feeling superior in their particular strong areas and

everyone is then proud to be working with such good people who are not a threat

to their own self-esteem. The practical way to do this is to begin by stating

the attributes for a particular job when you ask for a volunteer. That way

everyone is both self-evaluating and evaluating each other for their strengths

and weakness. The person who volunteers will usually be the best and a good

leader will couch the attribute description with someone in mind. If the best

person does not volunteer, the one who does not will feel guilty for not

sacrificing for the cause. This person should then feel like they owe a debt to

the group in the future. If more than one volunteers, then both feel strong

about themselves in that area and paring them off should work if they can

respect each other because they share values. Picking one over the other needs to be

avoided if possible to preserve the pride of the weaker volunteer. All of this

occurs in front of everyone so pride and social standing has to satisfied and

can be satisfied if handled honestly with an awareness of the role of pride.

It is tempting to ask someone in private to take on a particular task, but this

is asking for trouble if others find out and always sounds like flattery and

manipulation to the person being targeted. An absolute requirement here is that

the group needs to be diverse enough that most of the talents brought to the

table do not overlap to a great extent, and that the talent necessary to get

the job done exists within the group.

With an understanding of these principles,

the first step when taking over a committee or work group is to do your

homework. To understand how a group can get the job done you have to understand

what it is supposed to do, and the history of how it has been trying to do it.

This forensic work is critical. When I took over my faculty senate committee I

went to the bylaws to see what the group was supposed to be doing and then

looked at old files and minutes from when it was formed through to present day.

This revealed the key tasks that were not being done, one set of activities the

group engaged in from the start that went beyond the mandate, and most

importantly, identified the ethos of the committee. Identifying this overarching

ethos, or higher goal that motivated people to join, and that manifested

repeatedly in directing the committee’s actions and discussions was the single

most important factor in succeeding. In the case of WACC, it is improving how

writing is taught. Thus, I identified the ideal that the members had in the

past and would in the future sacrifice their time and effort to achieve.

The next step was to get practical.

The number one complaint about most university meetings is that the meeting was a waste of time. So a chair must make sure that each

meeting actually gets something done. This requires being organized, naming and

assigning tasks, and assessing and following up on those tasks. A chairs

greatest friend here is an Excel spreadsheet. Not wasting time also requires a

ruthless directing of all conversations during the meeting to prevent being

sidetracked. Some people are better than others at this. The difference comes

down to being undistractible and to not being afraid of being rude. The chair

needs to be aggressive at cutting people off by saying we need to get back on

topic. I have a terribly rude bad habit of interrupting and talking over people

when I think they are not getting to the point. This annoying impolite flaw in

myself has served me extremely well when running meetings.

My other practical advice is to

document everything.

1) Take good minutes yourself (as

chair) and always have an agenda circulated before each meeting. We started out

with someone else taking the minutes, but I later found that taking the minutes

myself allowed me to reflect on what was said and to have a better grip on what

was going on. It allows a better focus for the group to see what is happening from

one mindset (the chair) than from two (the chair and the note taker). Circulate

the draft minutes early to get the alternative points of view and incorporate

those into the final minutes.

2) One trick that makes all of the

differences is use the word ACTION in bold in the minutes and

agenda documents. When anyone is supposed to do anything put that person’s name

and what they are supposed to do after “ACTION:”. Do this for both

the minutes and agenda and make sure that person is called upon in the next meeting.

People will tend to do their actions either right after a meeting or right

after the next agenda is circulated. Hence, circulating the minutes quickly and

the agenda a few days before can help maximize completion of tasks.

3) Set up a realistic timeline to

meet the goals. I find that spreadsheets can be especially helpful here. In our

case, we set up a schedule spanning several years to dig out and catch up with

course renewals. We were able to stay on task and get the job done by setting

up a doable number per semester and scheduling ahead.

4) Stay true to your overarching

goal. When we identified improving the teaching of writing as our number

one goal, then making that happen drove all other thinking in setting up the

course renewal process. Instead of just ticking off boxes and thinking in terms

of completing the tasks, we asked how can use this task to help faculty improve

their teaching. My forensic work also revealed long-standing efforts to improve

teaching pedagogy that fell outside of the senate bylaws establishing WACC.

This aspect was ultimately added to the bylaws as one our official duties.

I realize that I had it easy

serving on a committee with a clear goal that all academics can get behind. It

would be much harder with committees like General Education where differing

philosophies and self-interests make it difficult to agree to common goals.

More mundane busy work type committees can also present a challenge to find a

higher ethos. At the other end of the spectrum is the challenge for extremely high-level

group tasks like forming university vision statements. In both of these cases,

there is the temptation to break it down into unmotivating tasks that need to

be done. The trick is to understand that there can be only one over-arching

high-ideal ethos and to not default to listing several practical outcomes. The

question every committee, group, or community member will ask before doing

anything is, is it worth making a sacrifice of my time and effort? A leader can

expect only naked self-interest unless they can articulate some higher ideal

the whole group believes in.

I am being so crazy after reading you.

ReplyDeletenehanetinblogEntertainments and enjoyments serviceshtml

This is a dream for everyone and every living things.

ReplyDeleterabiacoinloha mandi servicehtml